Complex post-traumatic stress disorder (C-PTSD) is a relatively new diagnosis for understanding how past events can impact our mental health in the present. If you’re struggling with difficult symptoms, you might have wondered if they could be due to complex trauma.

Complex trauma involves experiencing a series of events of a threatening or horrific nature, where escape is difficult or impossible. These events overwhelm an individual’s capacity to control or cope with the stressor. They can occur in childhood or adulthood, and could include (but aren’t limited to):

- Domestic violence

- Physical abuse

- Sexual abuse, harassment, or assault

- Neglect or abandonment

- Racial, cultural, religious, gender, or sexual identity-based oppression and violence

- Bullying

- Kidnapping

- Torture

- Human trafficking

- Genocide and other forms of organized violence

Those with complex trauma develop post-traumatic symptoms such as flashbacks, avoiding reminders of the events, and feeling constantly “on edge” or hypervigilant. But due to the prolonged and pervasive nature of the trauma, those with complex trauma develop additional symptoms that are important to recognize.

The first is trouble with affect regulation. This means they might have trouble calming down after a stressor or have strong emotional reactions. On the other end of the scale, they may often feel emotionally numb, or not able to experience positive emotions such as joy.

Secondly, individuals with complex trauma struggle with negative self-concept. This means they often have strong beliefs that they are worthless, or a failure. They might feel intense guilt or shame in relation to these beliefs.

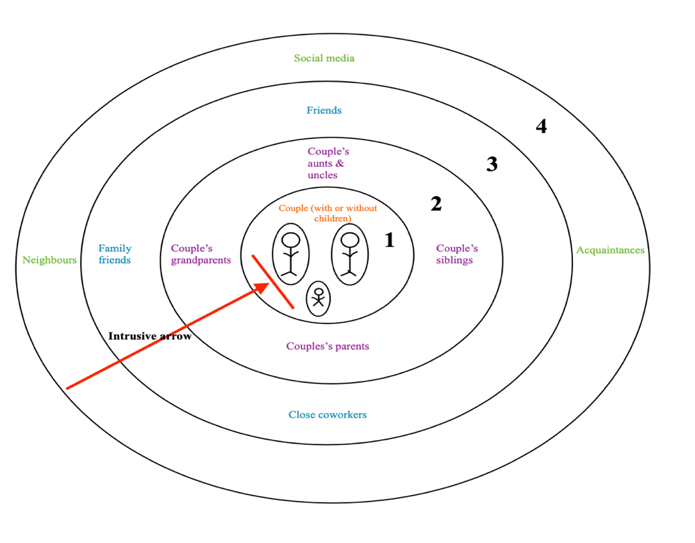

Finally, individuals with complex trauma often have issues in relationships with others. They might have trouble sustaining relationships and feeling closeness to other people. They might have short, intense relationships, or avoid relationships altogether.

Complex trauma often occurs across generations (sometimes referred to as intergenerational trauma), due to a lack of resolution of previous traumas and prejudice and discrimination that results in the oppression of entire families and groups.

Always consult with an experienced mental health professional if you believe that you may have complex trauma or another condition. Regardless of the cause of your symptoms, there are many treatment options available that can help you achieve your goals and feel better.

Camille Labelle, BSci, is a therapist working at the Centre for Interpersonal Relationships (CFIR) under the supervision of Dr. Lila Hakim, C.Psych. They provide individual therapy to adults who have experienced single-incident or complex trauma or are seeking support for other mental health conditions such as anxiety or depression. They use an integrated approach including emotion-focused therapy (EFT) and cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) to empower people to process their experiences, understand their reactions, and change their lives.

References

Ford, J. D. & Courtois, C. A. (2020). Treating Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorders in Adults, 2nd ed: Scientific Foundations and Therapeutic Models. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

World Health Organization. (2019). International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (11th ed). https://www.icd.who.int/